Small Beginnings

Like a mustard seed – the Methodist community had a small beginning. None of those involved then could possibly see what a dramatic future would face the church in Hong Kong and China. It was the vision of a few people who saw the possibilities ahead but faced, initially, negative responses from the counsels of the Methodist Church. That said, in the 1840s the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society (MMS) was already overcommitted across many of the countries of the expanding British Empire.

The first person to bring the request for a missionary to the attention of the MMS was Rowland Rees, attached to the Royal Engineers and stationed in Hong Kong. He held a Class Meeting in his own home in Stanley for soldiers stationed here. Seeing the need he wrote, as early as 1844, requesting that Methodist Missionaries be sent to all the five treaty ports including Hong Kong, and he sent a subscription for the work. At the Conference of 1846 the Methodist statesman, Revd Dr Jabez Bunting, noted the impossibility of such a new and great venture.

It was George Piercy who broke down the reluctance of the committees. A local preacher from England with a heart for China, he was determined to go at his own expense. Piercy had grown up in a farming family in Pickering, a small market town in Yorkshire, and could turn his hand to many things. He wanted to become a mariner but this did not work out. He spoke of himself as coming ‘fresh from the plough’, and threw himself into this great adventure. He had few qualifications, ‘except a believing heart, a firm spirit, and an inflexibility of spirit not to be thwarted by absolute impossibilities.’

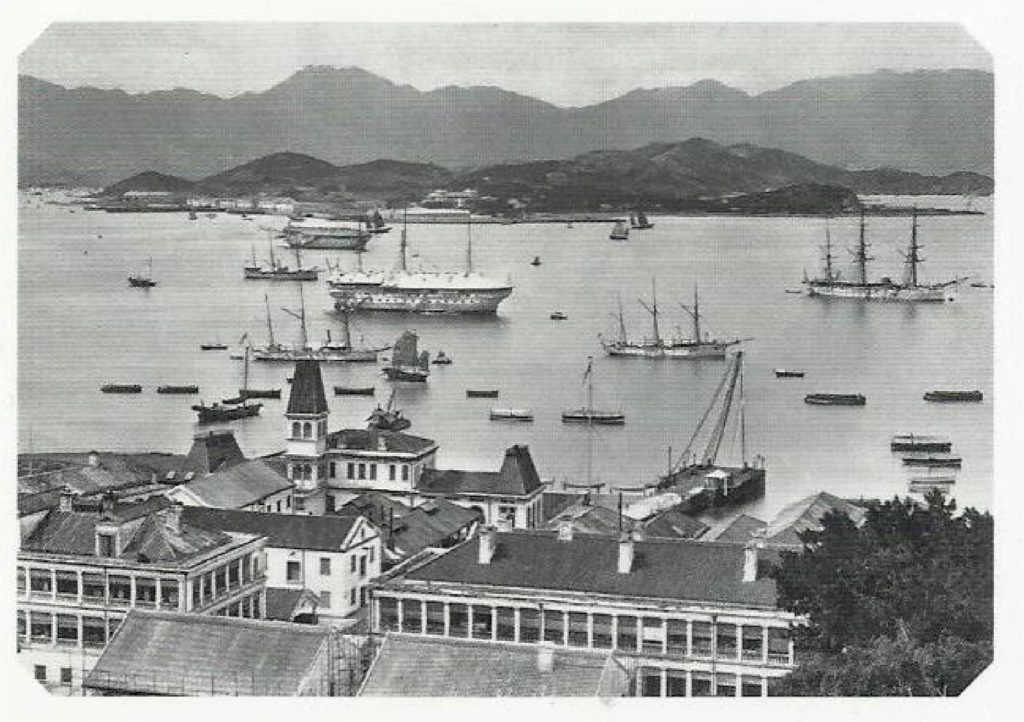

Undaunted, he set himself to study Chinese and sailed for Hong Kong in the autumn of 1850, probably working his passage. He arrived on the 31 January 1851. This fragrant harbour had, by then, been a British protectorate for ten years and Piercy found service men and government officials who had Methodist roots and wished to join in worship. It seems that a small society was formed almost as soon as he arrived and began to flourish using a building for worship at Magazine Gap.

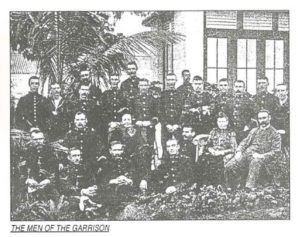

Inevitably the numbers fluctuated depending on the servicemen who were stationed in Hong Kong. All servicemen at that time would be required to attend a Church parade and service on Sunday. Most would go to the Anglican parish, but Catholics and Methodists who declared they were Wesleyans when they joined up, would be able to able to share in worship in Methodist Churches being established around the Empire.

Piercy’s fiancée, Jane Wannop, followed him out to Hong Kong and they were married in 1853 in St John’s Cathedral. It is not clear how he earned his living at this time. He desired to enter mainland China, but discovered that the Chinese language he learned in Hong Kong was not understandable even across the water in Kowloon. So working in mainland China would require starting all over again.

The Methodist Missionary Society relented, and in January 1853, they ordained and sent two freshly trained ministers from Richmond College, London, to join Piercy. William Beach and Josiah Cox arrived carrying a letter of ordination for George Piercy and elaborate ‘Instructions to the Missionaries appointed to commence a Mission in China’. He was ordained without further training or indeed a furlough but his contribution in Hong Kong was the establishment of the Methodist Society among service men. It was in that year that the first Synod of the Canton District was held. Josiah Cox wrote, ‘It did not seem a very imposing affair – three young men consulting over certain papers in a private room.’

So it was that the Revd George and Mrs Jane Piercy set off for Canton (Guangzhou) where they set up a church, with a school and girl’s boarding school attached. Piercy learned Chinese, Cantonese, from Mr Fat Leung, and mastered both speech and writing. He translated Pilgrim’s Progress into Chinese script. His work was brought to an abrupt end in 1856 when the Second Opium War broke out and his family, now with two small children, fled to Macau. Feelings were running high in Hong Kong with a large fleet and considerable force of soldiers being amassed for an invasion up the River Pearl. The situation on Hong Kong Island worsened that year following a failed attempt by the city’s Chinese bakers to poison the city’s European population and its amassed servicemen! Missionary work across China was dangerous, not helped by the expansionist policy of the European nations. When things were more peaceful, the Piercy family returned to Canton and he became Chairman of the District until 1882.

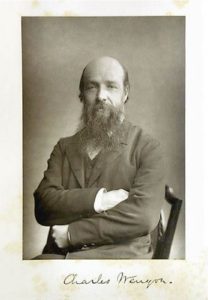

A significant leap forward in the mission of the church came with the appointment of the Revd Charles Wenyon – actually the Revd Dr Charles Wenyon, M.D., M.Ch., L.R.C.P. He had trained as a Doctor and specialised in tropical diseases prior to being an ordained Methodist Minister. Like many of his generation he was committed to China for life, forming churches, starting hospitals and medical stations. Wenyon succeeded Piercy as the Chairman of the South Canton District based mainly at Canton. He immersed himself in the culture of China travelling widely, and in 1896 he published an account of his travels; Across Siberia on the Great Post-road.

In 1885 Wenyon wrote to the Governor of Hong Kong, requesting a site to build a Wesleyan chapel for the use of sailors and soldiers, as well as civilians who were either government officials or merchants. The reply came eventually from London, written by Frederick Stewart Esq, the Acting Colonial Secretary: ‘I am directed by the officer administering the government to inform you that the Right Honourable the Secretary of State for the Colonies has been pleased to grant your request for a piece of land for the erection of a Wesleyan Church in the Colony, and I am to request you to be good enough to forward to the Excellency a sketch of the site which you propose to select for the purpose.’

Whilst waiting for the plot of land, the first missionary was appointed by MMS to Hong Kong, the Revd John A Turner. Previously no name had been given to this appointment in the Minutes of the British Conference, just the words, ‘One Wanted’. However in 1888 Turner was appointed to support the mission among the servicemen. The work was considerable; Turner reported that in 1890 there were 46 Declared Wesleyans in the army and 229 in the navy plus 30 native Chinese and 10 foreigners. By 1892 the services were held in the St Andrew’s Hall of the City Hall and there were 256 Declared Wesleyans in the army and navy.

Whilst waiting for the plot of land, the first missionary was appointed by MMS to Hong Kong, the Revd John A Turner. Previously no name had been given to this appointment in the Minutes of the British Conference, just the words, ‘One Wanted’. However in 1888 Turner was appointed to support the mission among the servicemen. The work was considerable; Turner reported that in 1890 there were 46 Declared Wesleyans in the army and 229 in the navy plus 30 native Chinese and 10 foreigners. By 1892 the services were held in the St Andrew’s Hall of the City Hall and there were 256 Declared Wesleyans in the army and navy.

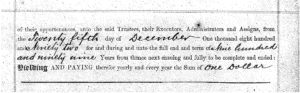

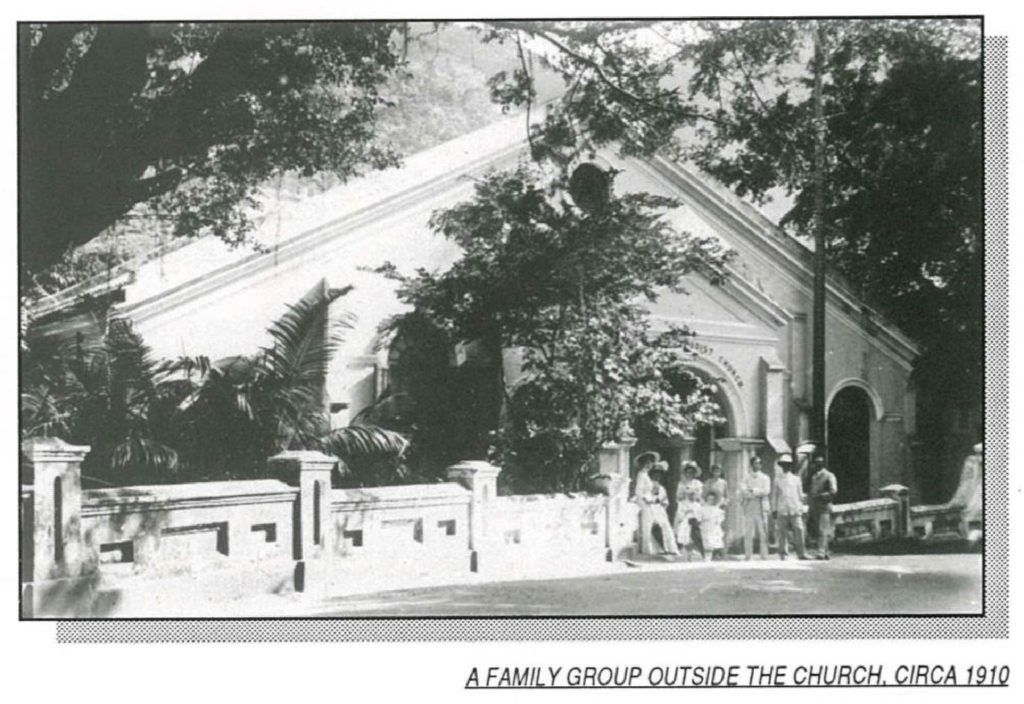

The land for an erection of a Wesleyan Methodist Chapel and Ministers Manse was eventually given in 1892. It was signed off by the Governor on the 25th December of that year, with a lease of 999 years at one dollar per annum. The Church was opened on Pentecost Sunday, 21 May 1893. The Revd William Musson was the appointed minister and he served for six years.

The chapel seated 300 and in torrential rain the opening services were conducted by the Revd Charles Bone, since Wenyon was travelling through China to England working on his book. The building cost ₤514 11s 6d of which the MMS paid ₤300. This Garrison Church served not only the army and navy personnel but also a few civilians and missionaries on furlough or travelling to China. From the beginning, the Church was known as The English Methodist Church.

The chapel seated 300 and in torrential rain the opening services were conducted by the Revd Charles Bone, since Wenyon was travelling through China to England working on his book. The building cost ₤514 11s 6d of which the MMS paid ₤300. This Garrison Church served not only the army and navy personnel but also a few civilians and missionaries on furlough or travelling to China. From the beginning, the Church was known as The English Methodist Church.

Revd Charles Bone, who succeeded Wenyon as Chair of District, wrote somewhat prophetically for the MMS Report in 1899:

For all signs of prosperity we thank God. Our heart’s desire is that the Holy Spirit may be abundantly outpoured upon European and Chinese staff, and upon all the churches of this District, that converts shall be multiplied a thousandfold, and the Church of Christ become a mighty regenerating power and a praise in this land of China.

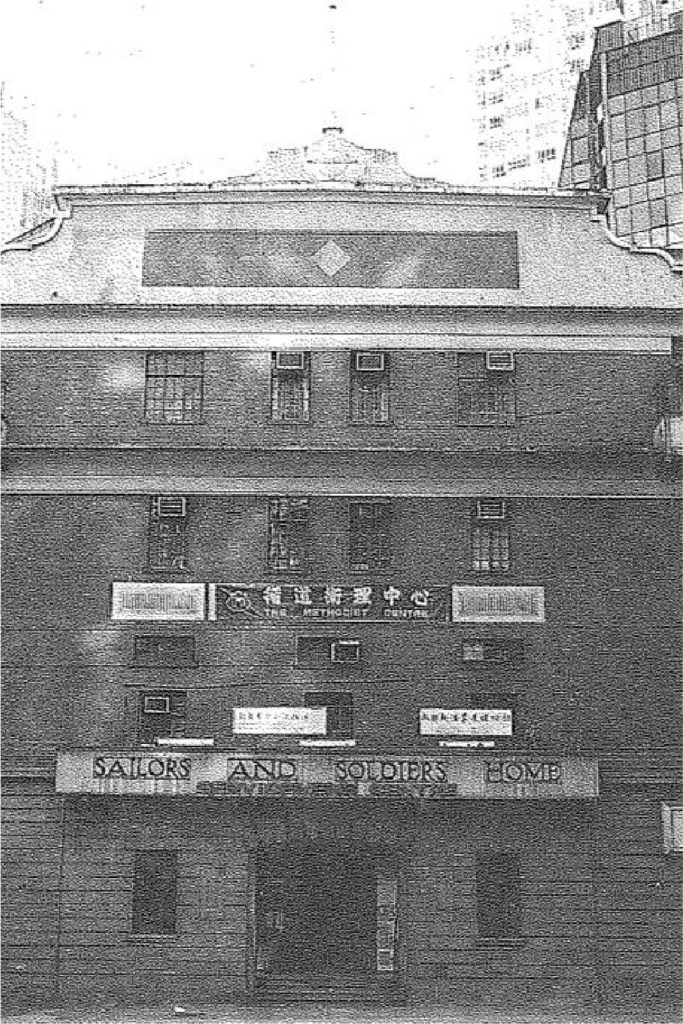

The Soldiers and Sailors Home

The English Methodist Church was the catalyst for much of the early work of the Methodist Church, Hong Kong. As early as 1895, Charles Bone succeeded in hiring two rooms in Arsenal Street for servicemen who were ‘Declared Wesleyans’. This work expanded and in 1901 a Soldier’s and Sailor’s Home was opened at No9 Arsenal Street providing 100 beds, a coffee bar, reading room, two billiard tables, a prayer room and meeting room. The Story of the Sailor’s and Soldier’s Home compiled by the Revd Man Kwok Wai tells the story in great detail. The plot of land of the first S&S Home was repossessed by the Government for road widening and the new tramway. The new S&S home was completed in 1927 at 22 Hennessey Road with a new manse for the minister at 75 Ventris Road. The Minister of the English Methodist Church also served the S&S Home right through until the 1990s.

The ministers of MIC used the S&S Home as a base for their offices, whilst living in one of 6 flats built by the MMS at 51 Barker Road. It seems they held services in the mornings with Sunday School, had Sunday Lunch at the S&S Home and held afternoon fellowship groups with a Sunday evening service at the Home.

There were three very significant ministers during this time, Joseph Sandbach , Edgar Hopkins and Cyril Clarke. They developed the work and encouraged community involvement.

The Chinese Churches

The first organised Chinese Methodist Church was begun in 1884 by a retired Chinese Methodist minister from Australia, the Revd Leung On Tong. In 1910 this church worshipped in a small shop in Aberdeen Street. In 1920 a house was bought in Caine Road and adapted for worship. Numbers continued to grow and in 1936 the Chinese Methodist Church, Wan Chai, was opened for public worship, with support from the English Methodist Church. The architect for all these projects, and that of Kowloon Methodist Church, was Arthur J. May who was a local preacher at the English Church and the S China District Architect.

The first organised Chinese Methodist Church was begun in 1884 by a retired Chinese Methodist minister from Australia, the Revd Leung On Tong. In 1910 this church worshipped in a small shop in Aberdeen Street. In 1920 a house was bought in Caine Road and adapted for worship. Numbers continued to grow and in 1936 the Chinese Methodist Church, Wan Chai, was opened for public worship, with support from the English Methodist Church. The architect for all these projects, and that of Kowloon Methodist Church, was Arthur J. May who was a local preacher at the English Church and the S China District Architect.

On the 26 Nov 1926 the bungalow, No 24 Chung Chau, was handed over by Randall Vickers and Mabel R Vickers to the Missionary Society in ‘natural love and affection’. Now known as Wesley Lodge, and it is part of the Methodist Church, Hong Kong.

The Japanese Invasion

The occupation took place on Christmas Day 1941 and the Home and the English Church were closed forthwith. The Church was in fact used to stable horses for the Japanese officers, which is why it may have taken until 1947 to be ready to open again! The home had various uses but was ransacked at the end of the war.

The ministers, significantly Revd Joseph E. Sandbach, were interned at Stanley with many of the leaders of Hong Kong society. Sandbach was appointed to the management committee for the prisoners and his ministry was greatly admired. He had come in 1937 and remained until his retirement in 1960. The selfless service of Revd Sandbach and his Assistant Minister Revd Alton were an effective and admired ministry among the 3000 prisoners. Man Kwok Wai notes, ‘Their selfless service and witness gave credit to Methodism. One of the internees, Mr N.L. Smith became the Colonial Secretary after the liberation and he was extremely helpful when Sandbach approached the Government to apply for a plot of land to build a church and school in Kowloon (1947-8).’

Education

From the time when Wesley founded his first boy’s school in Bath (England), education has always been one of the main interests of the Methodist Church. It is not therefore surprising that Piercy started a school and boarding house for girls in Canton. In Hong Kong, by 1896. the Methodists were offering education to 500 scholars in schools supported by a government grant. To lead this work a ‘Chinese teacher of more than average ability’ had been hired. MIC, as it developed, handed the work of education to the Chinese churches. Today, the Methodist Church, Hong Kong has 8 Secondary Schools, 11 Primary Schools and 12 Kindergarten and Day Nurseries.

Relationships with other Churches

As with many places, the ebb and flow of ecumenical relationships are dependent on the way ministers of various denominations actually get on together. During the early days there was a good relationship with Union Church, but during British negotiations between Methodism and The Church of England in the 1960/70s, Cyril Clarke was much closer to the Anglicans. Happily, today the relationships across the denominations are very good. The International Pastors Prayer Meeting covers over 40 churches which reach people groups from across the world who come to work in Hong Kong.

MIC is a full member of the Hong Kong Christian Council, and the Hong Kong Evangelical Fellowship – so MIC bridges all kinds of perceived chasms, and therefore its ministers participate in all kinds of meetings! The most significant relationship, of course, is that MIC is a full part of the Methodist Church, Hong Kong.

A Hong Kong Methodist Church

In 1987, at the Annual Conference of the British Methodist Church in Portsmouth, England (where both Revds Lo Lung Kwong and Howard Mellor were representatives), the negotiations were completed for what was known as the ‘Hong Kong English District of the Methodist Church’ enabling it to become a full partner in the Methodist Church, Hong Kong. Until that time the English Speaking Circuit had remained under the jurisdiction of the British Conference. Lo Lung Kwong indicated that ‘because of the language, history, background of the church members, and also the need to employ pastors from English speaking countries, this church was under the “one country, two systems” umbrella.’ Section 8a of the Constitution of the Methodist Church, Hong Kong allows for flexibility even today. The Portsmouth decision paved the way for the incorporation of MIC into the Methodist Church, Hong Kong from the 1 September 1988.

In recent years there has been a deliberate approach to bring the policies of MIC closer to that of the Methodist Church, Hong Kong. Hong Kong is the home, the place of work, the community in which the mission and ministry of MIC takes place. It is vital that the MIC sees its future commitment as a full part of the Methodist Church, Hong Kong.

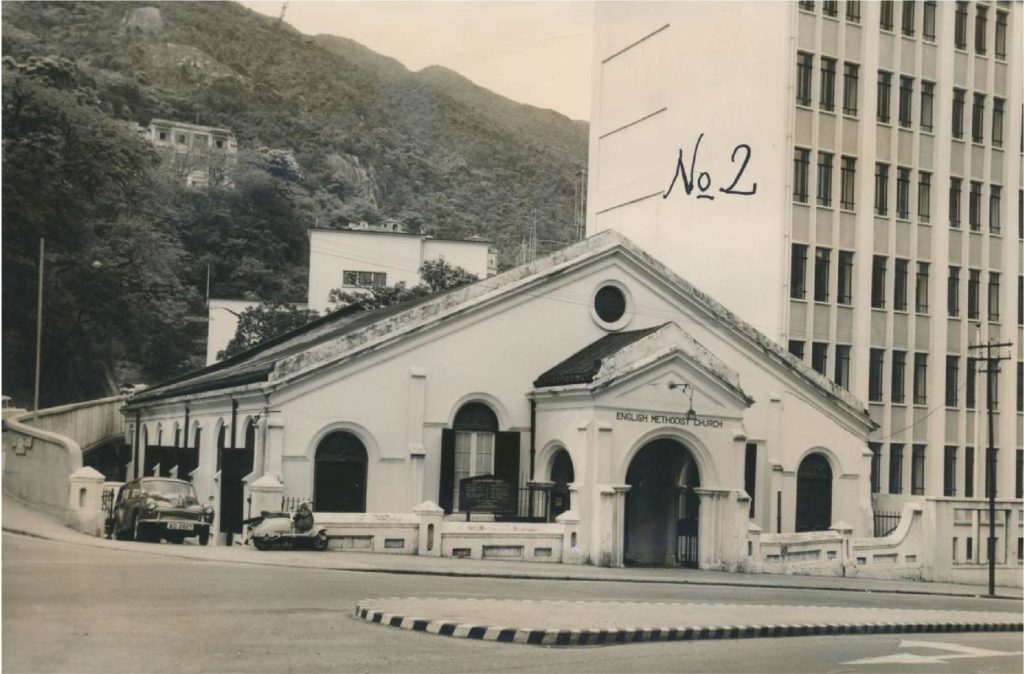

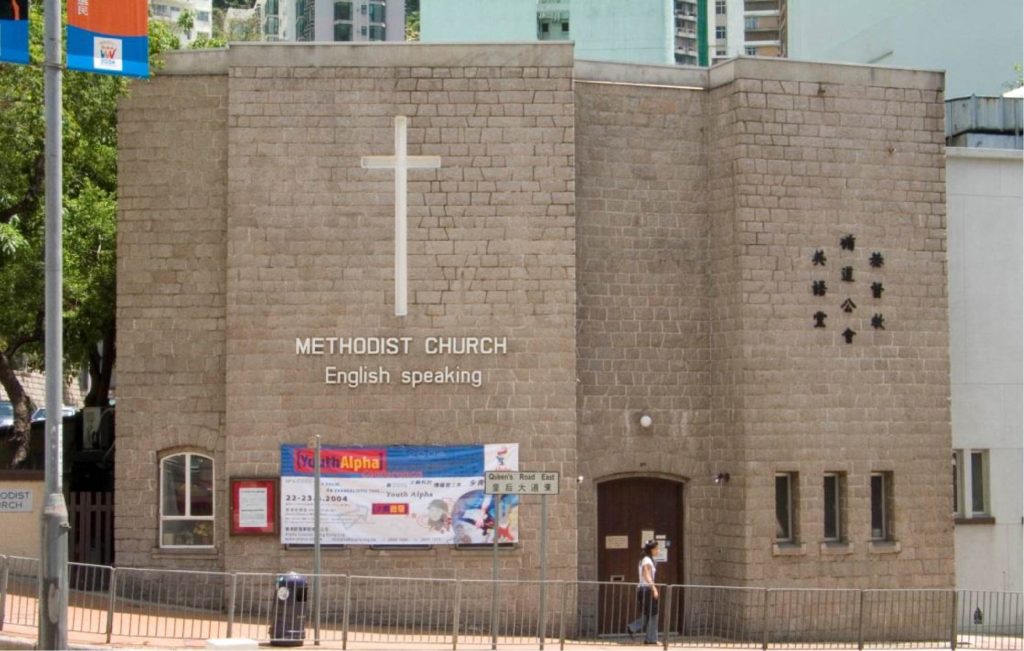

Over time the change of name of the church has mirrored the church’s understanding of its mission. First of all this was the English Methodist Church, also known as the Garrison Church, serving servicemen. Then as the number of civil servants increased, the new church in the 1960s was known as the Methodist Church (English Speaking), acknowledging that there were, by now, many other Methodist Churches in Hong Kong. In 2006 the church, acknowledging the change in Hong Kong of 1997, wisely changed its name to the Methodist International Church Hong Kong through a decision made in the Conference. Today we say that we have in our congregation people from every continent and many nations.

China Today

Much is being written about the exponential growth of the church in China. There are facts about Christianity in China which are both intriguing and challenging. The Amity Press in Nanjing has just celebrated printing 100 million bibles, most in Chinese, but also in many languages to be distributed all over the world. The State Administration of Religious Affairs keeps a close watch on the church, but both the Three Self Patriot Movement and the China Christian Council are flourishing. In November 2012 MIC was represented by Revd Jesus De Los Santos and Revd Howard Mellor, as part of a study tour to churches in Wenzhou where about 10% of the population are baptised Christians.

We visited large church buildings apparently bursting with Christians. The picture is of the then unfinished church in Luishi, Wenzhou, which will seat at least 4,500. The effect of the growth on Christianity in China with its close links with Hong Kong means that it is vital to provide Putonghua services and eventually support for mainland ministers and congregations groups with training, retreats and pastoral support. The Putonghua congregation of MIC is just the beginning of what could be a dynamic future ministry.

We visited large church buildings apparently bursting with Christians. The picture is of the then unfinished church in Luishi, Wenzhou, which will seat at least 4,500. The effect of the growth on Christianity in China with its close links with Hong Kong means that it is vital to provide Putonghua services and eventually support for mainland ministers and congregations groups with training, retreats and pastoral support. The Putonghua congregation of MIC is just the beginning of what could be a dynamic future ministry.

Outreach

The work of the English Methodist Church with service personnel was typical of the desire of the congregation to reach out to those in need. It is also part of the Wesleyan DNA, Wesley may have preached thousands of times in church and open air, often using his favourite text, ‘Flee from the wrath to Come!’ But he also opened orphanages, started schools, wrote a book on medicine, Primitive Physic, and offered it free to the poor, while charging the rich. He opened what preaching houses they had so women could come in and weave or knit items for sale and provide for themselves and their families. This fusion of preaching grace and doing justice is deep in the soul of Methodists.

Originally of course the focus of the work of the English Methodist church was among the service personnel who came to Hong Kong. Following the end of National Service around 1960 the energies of the church were channelled in other directions. The congregation was encouraged to participate both as individuals and as a church in needful causes within the community such as clinics and schools in the Kowloon Walled City, or at the developing Epworth, Asbury and Wesley Villages built for refugees fleeing conflict in mainland China.

The archives also indicate that members of the church were involved in the Leper Colony on Hay Ling Chau Island; the Heep Hong Society for Handicapped Children and the Rennie’s Mill Student Aid Project which later became the H.K. Student Aid Society. Some former members came back to visit MIC in March 2013 to celebrate 30 years of their group. These charities were enthusiastic about the commencement of the Methodist Study Trust started in 1984 by Barrie Wiggham and which continues to this day, helping students from poor families to access education.

This legacy of outreach continued with ministry to various national groups. There is photographic evidence of a fellowship for Indian Christians which must have been in the 1970s. Similarly the commitment to assist as the Vietnamese boat people arrived in Hong 16 Kong, all flow from this understanding of the gospel in truth and action.

When the Vietnamese boat people came to Hong Kong the Revd Barry Prior encouraged the church to be involved in caring for the refugees. The Minutes of the Church committees reveal the way the church came alongside the imprisoned communities and sought to help them. There are copious notes and a considerable correspondence with government officials seeking permission to allow the church to take Vietnamese children from High Island Camp, Sai Kung detention centre, on outings.

Filipino Christian Community

The Minutes of the Annual Church Meeting indicate that in 1980 there was a ‘Filipina Fellowship’ which the following year reported 50 women involved. It is clear from personal accounts, that it was the desire of the Revd Norman Dawson and his wife Marion to reach out to the growing number of Filipino Domestic workers. His sudden death in November 1981, after only 15 months in Hong Kong, slowed 17 the process down. The archive shows that the work began on or even before 1980 but it was led by Europeans.

The Filipino Fellowship marked the beginning of the work in 1984 which was when the leadership, and therefore its ownership, was passed to a Deaconess, Ruby Lamigo who was working as a domestic worker. The history of the Filipino Fellowship written for the 25th Anniversary of the Filipino Fellowship, 2009, highlighted the contribution made by Urduja Rhors and Cecilia Rodriguez. The work grew quickly and the Filipino Fellowship developed its variety of service and ministry. Working in Hong Kong was Revd Daniel Arichea who with his wife Grace supported the fellowship. It was in 1991 that the Revd Anacleto Castillo was appointed as an ‘In-bound Missionary’ from the United Methodist Church in the Philippines to serve as Associate Minister at the Methodist Church Hong Kong and appointed to lead the Filipino ministry at MIC.

During the 1990s there was a home called ‘Harmony House’ in the Hamilton Block, 42c Kennedy Road, for the use of Filipino women whose employment had been abruptly terminated. The Filipino Fellowship developed a system of governance which was parallel to the Church, though not under the governance of the Church Council. Under the guidance and leadership of Associate Minister Revd Jesus De Los Santos, and under the authority of the Church Council, the Filipino Ministry of MIC was developed. This has resulted in a significant growth of the work among the Filipino community in the last few years.

As a result of wide-ranging consultations leading up to the ACM of 2013, it has now been decided to bring to a close both the Filipino Fellowship and the Filipino Ministry and to form one united ministry for Filipinos called the Filipino Christian Community (FCC). The proposal had been discussed by the Filipino Leaders, which included both groups, and was placed before the General Assembly of all the Filipino Members of MIC in April 2013.

The decision to formulate the FCC with five focus groups considering Discipleship, Outreach, Fellowship, Education and Worship was agreed unanimously. The Annual Church Meeting of MIC, in May 2013, concurred and the new united approach was instituted with immediate effect. The newly formed FCC leadership will meet for the first time on 2 June 2013 but its anniversary will recognise the heritage of over 29 years. This decision draws on the work of, and is a significant testimony to the ministry of, Revd Jesus De Los Santos over the last nine years.

Redevelopment in the 60s and 70s

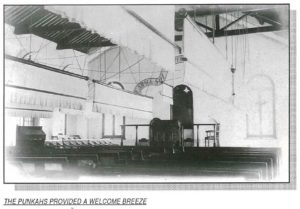

The need to expand the 1893 premises had been a growing realisation. The original building was a ‘low lying but grand old building in Chinese style’ with its main entrance in Queen’s Road East, a kind of porch with two rooms off to the side which were used by the Sunday School, and then the main body of the church. The windows along the side were relatively tall and narrow and carried heavy shutters for use in the event of a typhoon. A door behind the pulpit led to a small courtyard and the caretaker’s flat.

Originally the church had a number of large hanging, swinging fans, fixed to the ceiling, called ‘punkahs’ which were pulled by people outside the building by means of a rope from side to side to create cooling air in the building during the hot weather. Eventually electric fans were installed.

In the 1960s Cyril Clarke indicated that ‘This Church is not, and has never been, wealthy.’ He noted that the British Methodist Church had assisted the church financially, though after 1946 it had become self-supporting, ‘though only just’. The cost of the new church at that time was estimated to be HK$250,000, and this was clearly a significant amount. The Revd Cyril Clarke oversaw the final preparations for the demolition and rebuilding. The new building was completed in 1965 to fanfares in the community of Hong Kong.